This post was originally published on August 5, 2021. It has been updated a few times, lastly on March . The updates that appeared here earlier have been moved to the end of this blog post. The original content has been extensively updated.

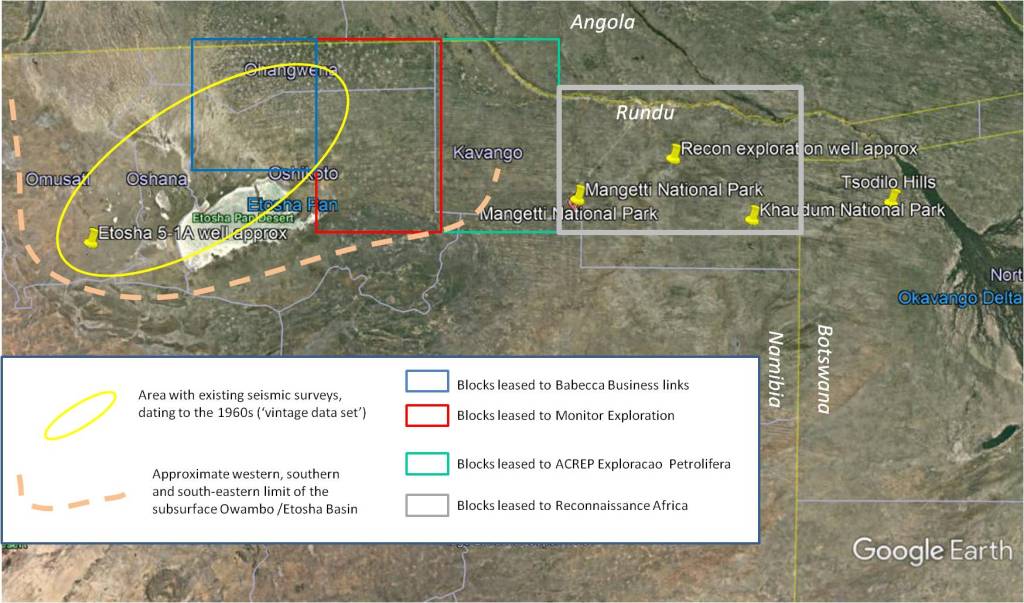

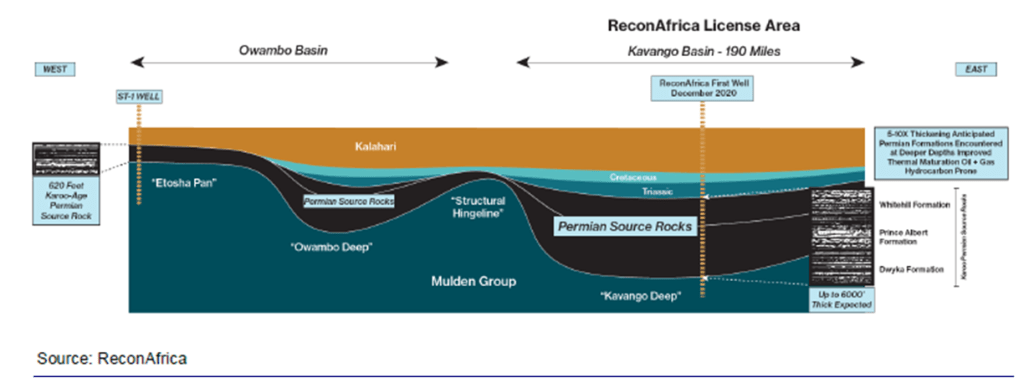

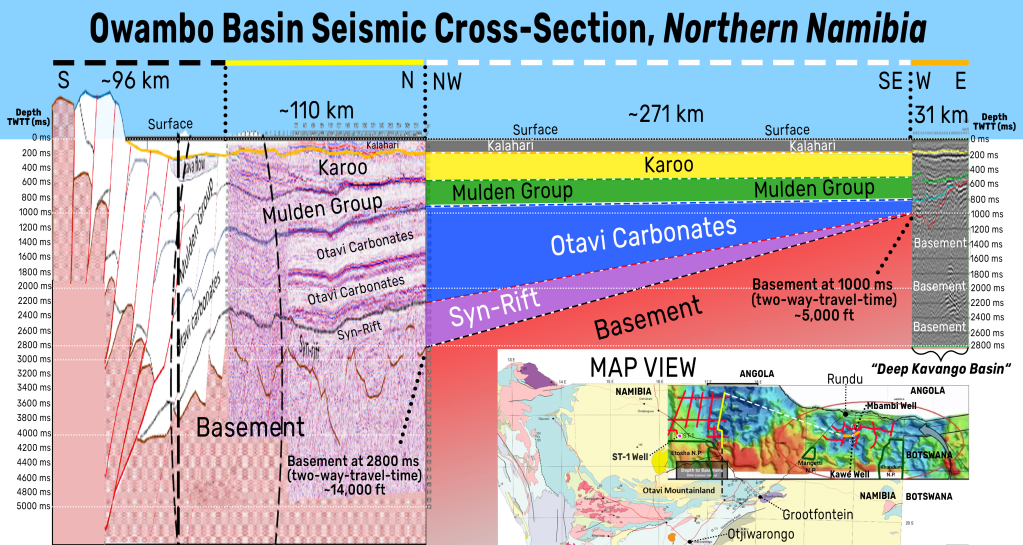

On November 5, 2021 ReconAfrica publicized its first three seismic lines. These lines represent 150 km of the 450 km the company collected. They can be viewed here and here. The data show that the Kavango subsurface “basin” is less than half the depth of the Owambo Basin to the west. This observation is in conflict with ReconAfrica’s claims of an ‘extremely deep basin’ in the Kavango area (which the company has called the Kavango basin).

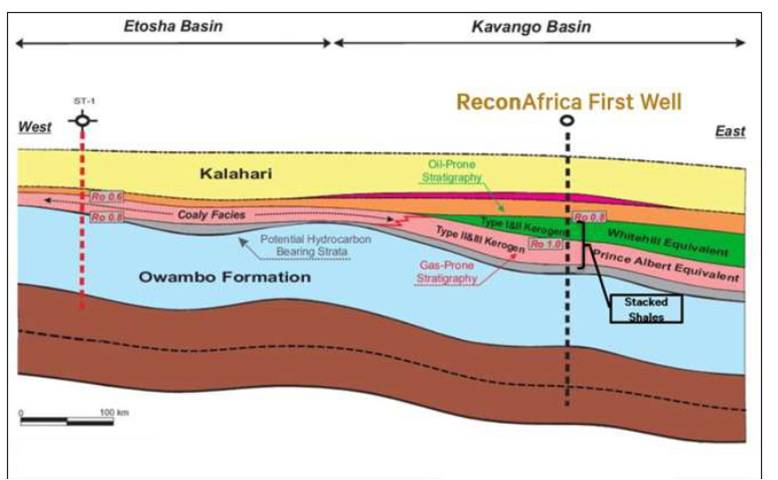

On November 16, 2021, Windhoek-based former petroleum geologist Matt Totten Jr gave a talk to the Namibia Scientific Society on the regional subsurface geology of the Kavango area. He demonstrated that there is no deep sedimentary basin and that ReconAfrica is (deliberately?) sowing confusion about its data and interpretations in order to stave off criticism of its operations. The talk is posted here. Matt Totten also demonstrates convincingly that ReconAfrica is drilling in the shallow eastern extent of the Owambo basin, something I had suspected all along and something of which ReconAfrica is accused of in a civil lawsuit filed against the company (see below). My own interpretation of the geology of this case is essentially the same as Matt Totten Jr’s interpretation. We have arrived at these conclusions independently of each other.

I have updated the content of my original post with this information, and I include my view of a talk that Dr James Granath, a petroleum geologist / consultant, who is based in Denver (CO) and is a director of ReconAfrica gave to the Houston Geological Society on October 25. I have also included comments on the recent article by James Granath and others, published in the Journal of Structural Geology.

Rolling Stone Magazine published an article by Jeff Goodell on March 26, 2023. The article quotes Dr Paul Hoffman, a well known geologist with a life time of research experience in Namibia. Dr Hoffman states that it’s naieve to think that there’s petroleum here. He was not aware of this blog post when interviewed. This makes three geologists (Matt Totten, Paul Hoffman and myself) coming to the same conclusion independently of each other: there is no basin here, there is no oil here.

Here is another recent article about one of the kingmakers behind ReconAfrica, mr Jay Park. Draw your own conclusions.

Original post, published August 5, 2021 last updated August 6, 2022

The title of this story is paraphrased from several headlines over the last few months. There was public outrage over the fact that Recon Africa was allowed to drill in elephant migratory territory in northeastern Namibia. Much was also written about the company being suspected of being dishonest about its objectives and basis for investment. The Globe and Mail’s journalist Geoffrey York (@geoffreyyork) wrote no fewer than eight articles about the issue (here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here; all other literature cited is listed at the end of this blogpost).

I was intrigued. What is actually going on? The media focused on supposedly shady investment practices, but not really on the geology. So here is a bit of geologic background. I only started reading about this case because I was disturbed that yet another Canadian resource company was reported to be behaving unethically in a country in the Global South. It seems there isn’t a day that we don’t read about these sorts of issues and that really disturbs me as a Canadian. Whereas the reporting focused on ReconAfrica’s shady practices of attracting investments, I decided to try to understand the geology, because that is the basis for investment.

I studied the geologic literature relevant to this part of the world, including literature pertaining to oil and gas (O&G) production. I conclude that ReconAfrica might be exploring in what they call the Kavango Basin (hitherto undocumented by anyone else), but that this area might also be an undocumented extension of the well documented Owambo/Etosha basin. Their exploration target is either a previously undocumented Permian shale interval, which would likely require hydraulic fracturing (fracking) in order to produce hydrocarbons or a deeper situated interval of Proterozoic Otavi Group limestones, which might or might not require fracking. It is unclear which interval they are targeting because they report both ‘shales’ and ‘carbonates’ (=limestones)’ as their hydrocarbon target rocks. The Namibian government states that it doesn’t allow fracking.

ReconAfrica filed an Environmental Assessment Report in January 2020 which states that elephants aren’t sensitive to the vibrations resulting from seismic exploration (Risk Based Solutions, 2020).

ReconAfrica has drilled 2 stratigraphic wells and has acquired 450 km of traditional 2D seismic data.

Background

First a bit of basics on hydrocarbon exploration. Hydrocarbons (either oil or gas) are locked in rocks in the earth’s subsurface. How do they get there?

- Oil may be formed when organic rich deposits (sediments) are buried and – given the right temperature and pressure regimes over time at great depths – become ‘cooked’ and convert into hydrocarbons. Rocks are buried and twisted and turned (folded) and broken up (faulted) because the earth’s crust consists of tectonic plates that move around while oceans form and close and in this way rocks get buried in the deep subsurface and/or are thrown up as mountains. What kind of organic rich deposits may be transformed into oil? Algal mats (cyanobacteria) or microscopic single cell organisms that float in oceans and lakes and are buried after the death of the organism (before being eaten by a predator). We’re talking billions of creatures and millions of years.

- Natural gas is formed when marsh and swamp deposits pile up as peat and are buried under sufficient pressure and temperature to become coal. Coal may then degas to yield natural gas, given the right conditions. This process too takes millions of years.

Both oil and gas, once formed, are very mobile and – given the right conditions – migrate from their position under pressure in the subsurface to a location with less pressure, if the geology allows it. And in this way hydrocarbons may become trapped in what’s called a “Reservoir”. A Conventional Reservoir is a rock that has enough porosity (holes) and permeability (connections between holes) to hold hydrocarbons. If the rocks surrounding the Reservoir don’t allow for further movement of the oil or gas, then the Reservoir is sealed. If you sink a well into a reservoir, you create an opening to a medium (the earth’s surface atmosphere) with less pressure than at depth and the oil or gas flows upward. Bingo!

Until about 15 years ago, most oil or gas was recovered from such Conventional Reservoirs, rocks with enough porosity and permeability (not every conventional reservoir produces easily, there are lots of ‘stimulation techniques’, but that goes too far for this blog post). Then came the fracking boom.

The organic rich rocks that contain oil and gas are called Source Rocks – as opposed to Reservoir Rocks. Source Rocks are usually shales, hence they have very low permeability, and hence the oil or gas stays put. These rocks are ‘tight’. Fracking (hydraulic fracturing) is a technology whereby you sink a well into a source rock and blast the subsurface with fluids under very high pressure. In that way you create artificial permeability so that you can force the hydrocarbons up your well. The Source Rock has become a Reservoir Rock through this technology. These are called Unconventional Reservoirs.

Hydraulic fracturing (fracking) is controversial because it requires a vast amount of water and chemicals injected under high pressure. After having done its job, the water is then contaminated and will have to be contained in tailings ponds until it’s cleaned up. It’s also really expensive because you need a lot more wells than when you produce from a Conventional Reservoir. Because even though you have created artificial porosity and permeability, the rocks are still tight and you need lots and lots of wells. And all those wells cause a huge disruption in the landscape (i.e. the earth surface’s ecosystems). Just travel to Bakken, North Dakota on Google Earth to get an idea. Because of these problems, fracking is banned in some jurisdictions (e.g. NY State, New Brunswick). The fracking boom has died down quite a bit because drilling so many wells is extremely expensive and the Returns On Investment (ROI) have been below expectations.

Namibia doesn’t allow fracking. This makes sense because it is a desert country, i.e. has water scarcity. ReconAfrica’s Area of Interest (AOI) in northeastern Namibia is a very thinly populated dry desert. What little water flows through there, is part of the headwaters of the iconic Okavango delta, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Geologists are employed by oil companies to predict where hydrocarbons (oil and gas) are ‘ahead of the drill’. Because drilling is expensive, companies acquire the maximum amount of geologic information using cheaper methods (hands-on fieldwork, seismic data, aeromagnetic data, gravity data) to get the best possible understanding of the geology before making the decision to drill.

Seismic exploration uses shock waves set off by the explosives that travel through the subsurface, bounce off differentially from rocks that have different densities and are then reflected back, thus forming an image of the stratigraphy (layers) and structure (folds and faults) of the subsurface. Good quality seismic data may also indicate the presence of hydrocarbons. In the distant past, before the availability of such advanced imaging technology, companies sometimes just sunk a well because they thought they understood the geology well enough. This process is called wildcatting. It doesn’t really happen anymore because the risk of wasting a lot of money on drilling in the wrong place is too high. ReconAfrica drilled two test wells (in May and June of this year) before collecting seismic data (July and August).

The Owambo-Etosha basin and eastern Kavango area

A sedimentary basin results when the earth’s crust descends and surrounding high land erodes and the sediments drain into the newly formed topographic low. The land erodes and the sediments are deposited in the basin. The sediments may contain organic rich intervals, also called strata.

Other sedimentary basins may form when, given the right latitude and ecosystem parameters, limestone forming reefs and algal mats accrete along the edges of tropical seas.

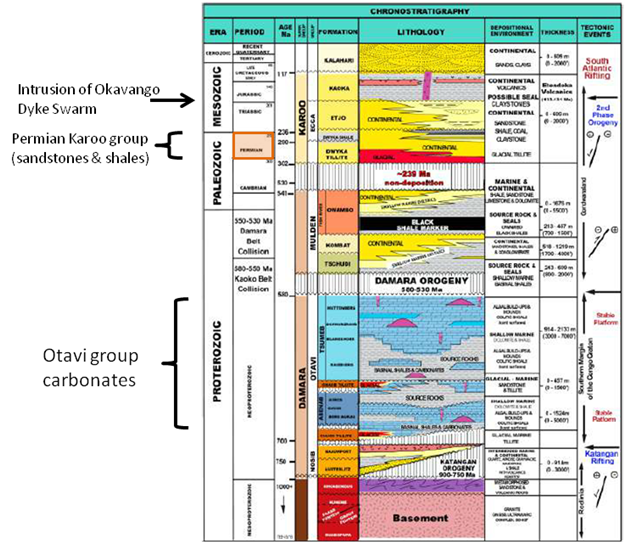

The colours are fairly intuitive. Blue-coloured intervals represent carbonate rocks (limestones), yellow and brown-coloured intervals represent various sandy and gravelly strata. Black intervals represent shale. Pink and purple indicate igneous rocks (rocks that come up from the depth of the earth’s crust, such as granites and basalts. These rocks never contain organic matter). Vertical-striped intervals mean that no rocks represent that time interval, i.e. there is a hiatus in the rock record.

The target interval in the Owambo/Etosha basin is the 500-700 million year old Otavi Group, consisting of mostly carbonate rocks (=limestones). The target interval in the hitherto undocumented Kavango basin is supposedly the 250-300 million year old Permian Karoo Group of sandstones and shales

Decades of research in southern Africa have resulted in a good understanding of its geologic history. One way to visualize that history is with a (schematic) stratigraphic column, which depicts the known stack of rocks from subsurface to surface in a certain region, plotted against time. It tells, schematically, what happened in that region over a long period of time. The stratigraphic column shown here covers 1 billion years of geologic history in the general area of the Owambo/Etosha Basin, indeed a very schematic representation.

The stratigraphic column doesn’t tell you whether the rocks are folded or faulted. In this figure, the three far right columns list the various depositional and mountain building events and the thickness of the different rock units. These columns add to the story.

The Owambo basin’s western extent is well known and documented, its eastern margin was never well known. Part of the reason is that the rocks are buried below a thick sequence of more recent Kalahari sands and part of the reason is that this area is still littered with land mines.

What is the history of hydrocarbon exploration in this part of the world?

The Owambo/Etosha basin was formed as a result of tectonic processes. It contains a thick pile of sediments and was explored for hydrocarbons in the 1960s and 70s. Seismic data were collected at that time and five wells were drilled. Four of them were dry holes, one well (Etosha 5-1A) had a bit of an oil showing.

The drilling at the time targeted the 500-700 million year old Otavi Group which consists of shallow marine algal limestones. There was no life on land yet in those days and life forms in the oceans didn’t have exterior skeletons (shells). These cyanobacteria built up mounds of algal material. If you wonder what that would have looked like, modern day Shark Bay (a UNESCO world heritage site) in western Australia is an analogue for that kind of environment. Although these rocks have been buried for a very long time, they didn’t go “through the oil window” (they didn’t get “cooked”) and no hydrocarbons were really generated in the Otavi Group, at least not in the western Owambo/Etosha basin.

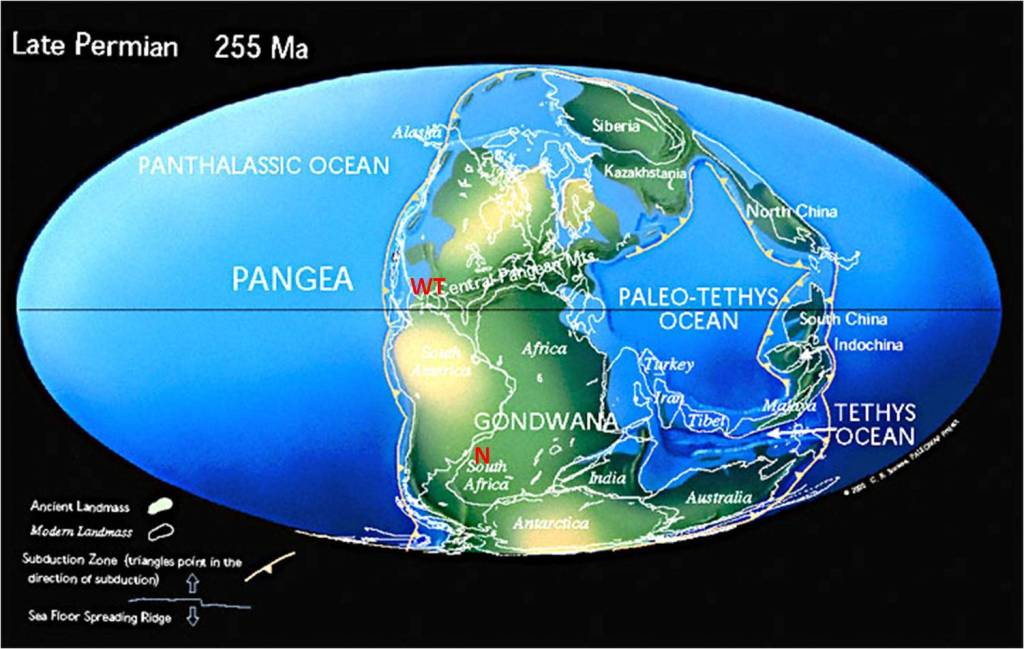

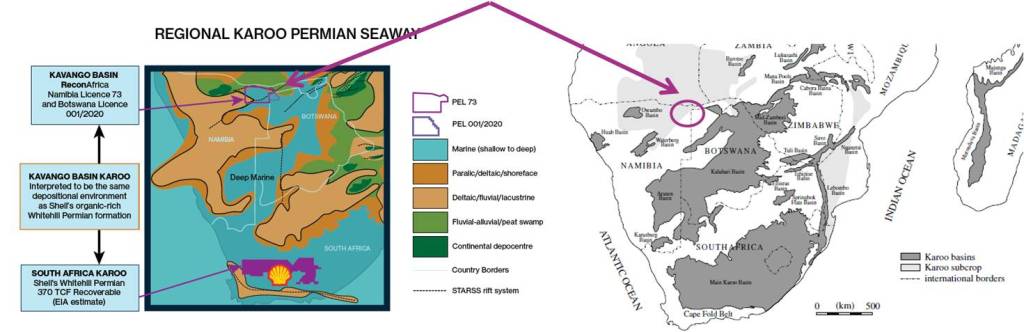

Millions of years passed after the deposition of the Otavi Group (lots happened, but too much to address here) and now we’re in the Permian, a geologic period that lasted from roughly 300-250 million years ago. At this point in time, what is now Namibia was situated at a mid to high southern latitude and the large Kalahari basin was formed. Most of the rocks here are deposited as sand and mud on land and in shallow bays and estuaries. The deep sea was far away, because this was the time of the supercontinent Pangea. These rocks are the rocks of the Karoo sequence. They have been studied extensively.

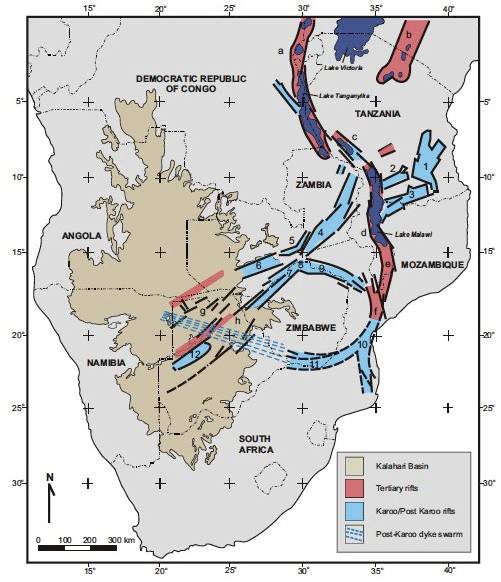

After the Permian, the supercontinent slowly began to break up. Great rifts formed in the earth (more or less the way the Great African Rift is formed now) and cracked the earth’s crust, forming localized deep basins.

By the early Jurassic, ca. 200 million years ago, continental break-up intensified and magma from deep down the crust welled up, forming so-called ‘dyke swarms’. One such dyke swarm is the Okavanago Dyke Swarm (ODS) which formed around 180 million years ago.

Several papers, a.o. those by Granath and Dickson (see references at the end of this blog post) suggest that the Karoo and post Karoo rift basins extend further into NE Namibia forming what they call the Kavango Basin. The existing literature doesn’t suggest the existence of such a basin: Corner (2000) even shows abrupt shallowing here. But a basin may of course have been missed in the past. The area was the site of guerilla warfare until 1990 and got riddled with land mines; it was therefore very inaccessible. More recently acquired aeromagnetic surveys have unveiled the presence of the Kavango Basin, at least according to ReconAfrica’s geologists. In a June 2021 webinar, Jim Granath suggests an intricate tectonic model for the Southwest African Rift systems, resulting in what we call a pull-apart basin, which is what he calls the Kavango Basin. I’ll come back to this proposal further down in this blog post.

What is ReconAfrica doing?

ReconAfrica’s founder and majority shareholder Craig Steinke stated that he found a “vintage set of data” and that this find led to the discovery of a completely new play (a play is a stratigraphic and geographic interval with comparable characteristics favourable for hydrocarbon production) in the Permian Karoo stratigraphic interval and that the discovery and analysis of this set led the company to position their stratigraphic wells (they brought the drill rig in all the way from Texas – during the pandemic). They filed their stratigraphic well reports but they didn’t include the log of the well “because they have no reserves”. This may be an odd statement, but it’s based on an independent evaluation (Sproule report, 2020) which uses only probabilistic methods in the absence of actual data. Quoting the Sproule report: “The leads on …. ReconAfrica’s leases …. land carry very high risk because all geological risk factors are poorly defined with almost no information available at the present time”.

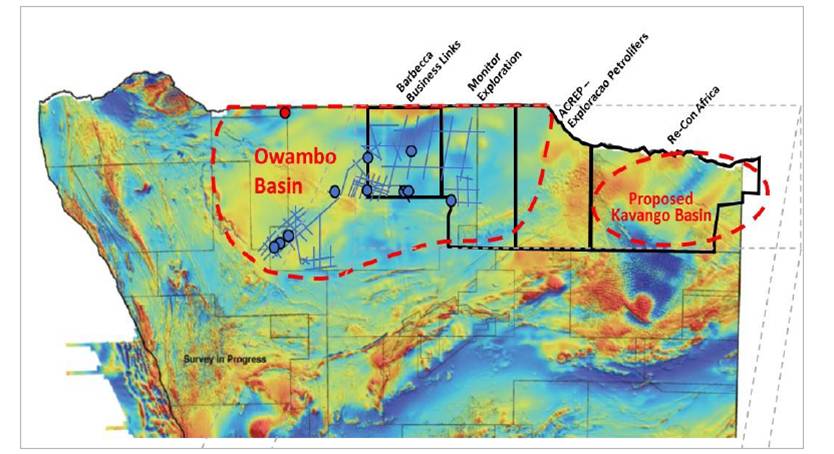

The aeromagnetic data is shown below. It is puzzling why this data set would get anyone excited about the Kavango area. Because the colours (darker blue for greater depth, lighter blue for shallower, brown for very shallow) show that the “proposed Kavango Basin” is shallower than the Owambo basin.

The Owambo basin was formed as a result of the collision of continental fragments more than half a billion years ago. Geologists call it a “Foreland basin”. A foreland basin forms as a reaction to a tectonic load elsewhere. Its width is determined by how the earth’s crust responds to a load. There is no evident Permian-age load in NE Namibia, 1300 km north of the Karoo basin, hence a deep basin here is physically impossible. Earlier exploration showed that the target rocks in the Owambo Basin (the Otavi Group limestones) were not oil-bearing and that exploration campaign was abandoned. A 1979 paper by Clauer and Kroner, using the well samples from this original drilling campaign, demonstrated that the rocks in the target interval experienced “low-grade metamorphism”, meaning that they experienced significant heat and pressure long after burial or – in lay language – these rocks were ‘cooked’ to the extent that any hydrocarbons evaporated out of them a long time ago.

Quoting the Environmental Assessment Report by RBS (2021): “Reconnaissance Energy Namibia has interpreted high resolution aeromagnetic data documenting a very deep untested Kavango basin with optimal conditions for preserving a thick interval of organic-rich marine shales in the lower portion of the Karoo supergroup. Reconnaissance Energy Namibia’s interpretation strongly suggests that the formational equivalents to the lower Ecca Group (Permian) will be preserved in the untested deeper portion of the Kavango basin. The company believes that these target sediments lie in a previously unrecognized Karoo basin along major trans-African lineaments that link NE Namibia to the better known Karoo rift basins in eastern Africa”.

This statement is in conflict with the company’s own published aeromagnetic map as is the figure below, which used to be featured on the company’s website, but has since disappeared.

Below is another schematic cross section published by ReconAfrica. This one also has no vertical scale. The seismic data now available give more detailed and very different interpretation. I’ll discuss these below. The figure shows that ReconAfrica is targeting the Permian age shale intervals of the Prince Albert and Whitehill equivalent Formations. The ST-1 well in the Owambo-Etosha basin had a small oil showing in Proterozoic Otavi limestones. The light blue Owambo Formation is part of the Mulden Group. The brown lowermost interval thus represents the Otavi Group. Note that the figure suggests that “things deepen to the East” a suggestion that is in conflict with the aeromagnetic data shown in figure 6. It is also in conflict with scientific literature, which doesn’t document the existence of the Whitehall (equivalent) and Prince Albert Formations in the subsurface of NE Namibia.

Below is a paleogeographic reconstruction of the area during the late Permian when the Whitehill and Albert Formation shales were deposited. To the left if a figure by ReconAfrica, to the right a figure from an authoritative comprehensive review article by Catuneanu et al (2005). That article doesn’t show any Whitehall/Prince Albert shales in the Kavango area (purple arrows). A more recent PhD dissertation (Werner, 2006) also doesn’t show the presence of marine deposits in this area.

Before we get to ReconAfrica’s well and seismic data, let’s look at data from another company in the area. Figures 3 and 6 show two other lease blocks. The blocks edged in red in figure 3 are leased to Monitor Exploration Ltd. MEL makes clear they’re exploring the Owambo basin. They state: “The Owambo basin is probably the most important area in terms of hydrocarbons exploration onshore Namibia. Its stratigraphy comprises rocks from Pre-Cambrian times till the Tertiary cover of the Kalahari Sands Formation with a total thickness up to 8,000m. Otavi Group, a Neoproterozoic carbonate platform, represents the main target”. MEL also states that “aeromagnetic data suggest that there are features associated with magmatic intrusions that may have affected the petroleum system.” Are they referring to the Okavango Dyke Swarm? Or are they referring to the younger Etendeka volcanics? MEL also published a seismic section. Matt Totten correlated that seismic section with the seismic sections of ReconAfrica. The result is shown here.

In between the two MEL blocks edged in red and the ReconAfrica blocks edged in grey are two blocks (edged in green) leased to ACREP, an Angolan Petroleum services company. ACREP completed its environmental assessment in 2017 and “started it survey of the Owambo/Etosha basin”. ACREP did a seismic survey in 2018 in their block (no 1818) according to ReconAfrica’s EAR (Risk Based Solutions 2020). Jim Granath shows this seismic line in his talk to the Houston Geological Society on October 21. It is reproduced on a small scale and it’s difficult to read, but the Otavi Group occurs at the same depth as in Matt Totten’s correlated section in Figure 10 and also at the same depth as ReconAfrica’s well shown below: at ca. 1,200 m depth. This is NOT a ‘deep basin’.

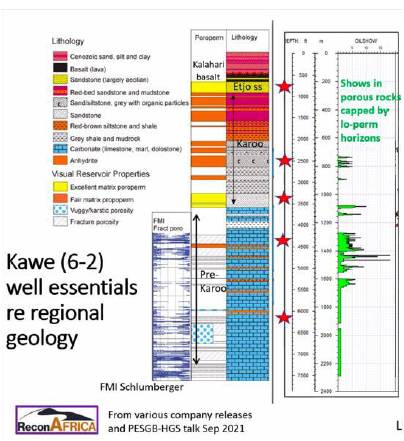

Above is the lithology of the 6-2 well as described by Ansgar Wanke. Dr. Ansgar Wanke is a German geologist who completed his PhD in 2000 at the University of Wurzburg on the tectonics of NW Namibia. From 2008 to 2019 he was a professor at the University of Namibia, after which he left to join ReconAfrica. I trust that he’s able to describe the lithology (the rocks) in the well accurately, i.e. I assume this is a correct representation of the sequence of rocks present below the surface in the Kavango area. So here we go: the Otavi Group Carbonates are encountered at about 1,200 m depth. This is a shallow basin with pathetic oil shows. When asked about the lithology of this well during the talk to the Houston Geological Society, Jim Granath says he “can’t answer” whether the lower Karoo was present and whether this interval is thick enough to generate an oil window. He also mentions they don’t know whether the prominent Mulden marker is present. Believe me, you wouldn’t miss that marker even on a lousy seismic line.

In his talk to the Houston Geological Society in November 2021, Jim Granath also mentioned that he had been in the field with Ansgar Wanke in NW Namibia. Together they came up with a complicated tectonic model that supposedly explains how the much older Rifts in NW Namibia extend into the subsurface in NE Namibia, leading to a very deep basin with lots of mature hydrocarbons. Jim Granath reported that they have submitted an article discussing this model to a special issue of the Journal of Structural Geology. This article came out in late June 2022 and I include a comment in the next paragraph.

I have studied both Granath’s online presentations (Fall 2021) and I can’t make head or tail of his tectonic model. I read a number of related scientific articles and there isn’t a single one that suggests at a hint of a possibility for his proposed model. There is no evidence of (Permian) Karoo-age rifting, but there is evidence of later (Jurassic) rifting (for example Modisi et al., 2000). Of course, someone will tell me that scientists always come up with completely new ideas and this is true. But those new ideas always have a basis in the scientific literature, sometimes in a parallel domain of science. Granath’s model seems to have no basis in the scientific literature and the graben structures that he postulates must be present below the surface in the Kavango area, are not observed on the available seismic data.

The long-awaited article by Granath et al (2022) may be a contribution to the geologic origin of the Waterberg Thrust, but it doesn’t provide any documented geologic evidence that underpins the hydrocarbon exploration program by Recon Africa in the Kavango area: the few off-hand references to the Kavango area serve only to whitewash the shoddy geologic underpinning of the Kavango hydrocarbon exploration venture. I include a longer comment on this article at the end

In this talk, Jim Granath also mentions “reef-prone lower Paleozoic units”. What?? The Otavi Group limestones are late Proterozoic, not Paleozoic and there is no evidence of any lower Paleozoic limestone units in ReconAfrica’s well, nor in any other literature. In answering the questions from the audience (it’s a zoom talk) he mostly waffles about what they’re encountering

There’s more that’s suspicious about Jim Granath’s activities here. In his talk to the Houston Geological Society he mentions that Craig Steinke came ‘sniffing for plays’ in about 2014 and “hinted he could get investment”. Jim Granath had never worked in southwestern Africa, but in 2018 he published an article arguing for producing both conventional and unconventional hydrocarbons in Sub-Saharan Africa. This article is not peer-reviewed, i.e. nobody has vetted the ideas he launched in it. Then in 2019 ReconAfrica starts its activities. I smell unethical practice here.

In their other literature, ReconAfrica also makes a big deal of how the Permian of the Karoo Group compares well, as an oil system, to the prolific Permian Basin of West Texas. The West Texas Permian Basin contains almost exclusively carbonates (limestones) and the area at the time was just north of the equator on the western margin of the supercontinent (see figure 4). Paleolatitude and thus climate and thus conditions for carbonate deposition in what would become West Texas were incomparable to those of NE Namibia at the time. But ReconAfrica also said they’re targeting the Whitehill and Prince Albert Formations, which are shales (i.e. not carbonates). These shales haven’t been encountered in the well and earlier literature (Catuneanu et al., 2005) didn’t show there was a basin there at all. Hence the Karoo-age sandstones in the well substantiate what existing literature demonstrated (there’s no basin, there are no shales, there was no “lake”). ReconAfrica also states something about favourable conditions of these shales (there are no shales!) in comparison with e.g. the “Bakken and Woodbine Formations”. The Bakken Formations are part of the Bakken Shale basin in the US Dakotas and the Woodbine Formation is a shale interval in the Gulf of Mexico subsurface in Texas. Both of these formations are tight shales, i.e. unconventional reservoirs and fracking has been used to produce oil from both (see Matt Totten Jr.’s talk about more on this topic).

Producing hydrocarbons from shales (the Whitehill and Prince Albert Formations) would require fracking. ReconAfrica doesn’t have a permit for fracking and Namibia says it doesn’t allow it. ReconAfrica had its potential resources evaluated by an independent resource evaluator, the Sproule company. The Sproule report (2020), based entirely on literature, public data, and probabilistic methods, also states that these Formations are tight (i.e. would require fracking). But seismic and well data don’t show that the Whitehill and Albert Formations occur here, which is in line with existing literature.

Note that the founder of ReconAfrica, mr Craig Steinke and one of the senior geologists, mr Nick Steinsberger both made a name in unconventional (tight, fracked) hydrocarbon production. And Jim Granath himself wrote at least two papers building the case for unconventional hydrocarbon development in Southern Africa.

No oil of any significance has ever been found in rocks (sandstones, shales) of the Permian Karoo Group further east in Botswana. One of the reasons for this absence of hydrocarbons may be explained by the presence of the Okavango Dyke Swarm (Le Galla et al., 2005). The Okavango Dyke Swarm is about 180 million years old. Its immense heat may have cooked the hydrocarbon rocks to the point that they got evaporated out of the rocks (‘devolatized’).

Conclusion

Viceroy Research (2021) blasted ReconAfrica’s enterprise for deceiving (potential) investors and from not being clear about whether they will need to use fracking. This claim is also made in the lawsuit that was filed against the company.

At this point in time (late November 2021) we are sure a deep Kavango Basin doesn’t exist. We also have seen that the oil shows in the 6-2 well are pathetic. Did ReconAfrica know this all along? Did Jim Granath invent his tectonic model to pump the stock and get a nice cash reward himself?

Aside from this, I imagine the company, staffed with fracking experts, knew all along that fracking is illegal in Namibia, but maybe they thought they could twist a few arms in what is a country with high levels of corruption (see for example here and here). Fracking in this part of the world would be completely and utterly irresponsible given its high water demand in this bonedry savannah area where local people depend on clean water.

The Namibian government wants to attract oil and gas development, arguably as “a bridge to net zero in 2050”. Namibia has all of 2.5 million inhabitants and is mostly desert. With the right public investment policies, the country can develop its required electricity infrastructure without having to resort to Oil and Gas development. The world is in a climate crisis and must transition to non-carbon energy as fast as possible. We all know that we can’t do that overnight. Producing existing plays during this “bridge period” is legit, but developing new plays in pristine parts of the world is disingenuous and inexcusable.

References

Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex and Reinhold Mangundu, October 14, 2021, Protect the Okavango River Basin from corporate drilling. Washington Post

Africa Good Morning, 16 July 2021, Geologist Matthew Totten on ReconAfrica

Baxter, J., October 8, 2021. A Calgary Company is drilling for oil in the world’s largest international wildlife reserves. These Nova Scotians are trying to stop it. Halifax Examiner

Catuneanu, O, H. Wopfner, P.G. Eriksson, B. Cairncross, B.S. Rubidge, R.M.H. Smith, P.J. Hancox, 2005, The Karoo basins of south-central Africa. Journal of African Earth Sciences 43, p. 211–253

Clauer, N. and A. Kroner, 1979, Strontium and Argon isotopic homogenization of pelitic sediments during low-grade regional metamorphism: the Pan-African Upper Damara sequence of northern Namibia (SW Africa). Earth and Planetary Science Letters, v. 43, p. 117-141

Corner, B., Crustal framework of Namibia derived from Gravity and Aeromagnetic data

Granath, J.W. and William Dickson, 2018, Organization of African Intra-Plate Tectonics.*Search and Discovery Article #30555, Posted March 12, 2018 . *Adapted from extended abstract prepared in conjunction with oral presentation given at AAPG/SEG 2017 International Conference and Exhibition, London, England, October 15-18, 2017.

Granath, J.W. and William Dickson2, 2018, Why not both conventional and unconventional exploration in Sub-Saharan Africa? Search and Discovery Article #30551 Posted February 19, 2018. *Adapted from oral presentation given at AAPG 2017 Annual Convention and Exhibition, Houston, Texas, United States, April 2-5, 2017

Granath., J.W., A. Wanke and H. Stollhofen, 2022, Syn-kinematic inversion in an intracontinental extensional field? A structural analysis of the Waterberg Thrust, northern Namibia. Journal of Structural Geology, v. 61

Haddon, I.G., 2005, The Sub-Kalahari Geology and tectonic evolution of the Kalahari Basin, southern Africa. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 360 p.

Hoak, T.E., A. L. Klawitter, C.F. Dommers and P.V. Scaturro, 2014, Integrated exploration of the Owambo Basin, onshore Namibia: hydrocarbon exploration and implications for a modern frontier basin. Search and Discovery Article #10609, Adopted from poster presentation given at 2014 AAPG Annual Convention and Exhibition, Houston, Texas, April 6-9, 2014

Le Galla, B, Gomotsang Tshoso, Jérôme Dyment, Ali Basira Kampunzu, Fred Jourdan, Gilbert Féraud, Hervé Bertrand, Charly Aubourg, William Vétel, 2005, The Okavango giant mafic dyke swarm (NE Botswana): its structural significance within the Karoo Large Igneous Province. Journal of Structural Geology, v. 27, p. 2234-2255.

Modisi, M.P. , Atekwana, E.A., Kampunzu, A.B., Ngwisanyi, T.H., 2000, Rift kinematics during the incipient stages of continental extension: evidence from the nascent Okavango rift basin, northwest Botswana. Geology, v. 28, no. 10, 939-942.

National Geographic Articles: October 28, 2020; October 29, 2020; January 28, 2021; March 12, 2021; May 11, 2021; May 21, 2021; June 25, 2021;

ReconAfrica News Release 1 and 2

Reeves, C.V., 1979, The reconnaissance aeromagnetic survey of Botswana – II: its contribution to the geology of the Kalahari. In: McEwan, G. (Ed) The proceedings of a seminar on geophysics and the exploration of the Kalahari. Geological Survey of Botswana Bulletin, v. 22, p. 67-92.

Risk Based Solutions (RBS), 2021, Draft environmental scoping report, Report to support the application for Environmental Clearance Certificate (ECC) for the proposed 2D seismic survey covering the area of interest (AOI) in Petroleum Exploration License (PEL) no 73, Kavango Basin, Kavango West and East regions, northern Namibia, 134 p.

“Sproule Report”: Kovaltchouk, A., Suryanarayana Karri, Cameron P. Six, 2020, Estimation of the prospective resources of Reconnaissance Energy Africa Ltd in Botswana and Namibia (as of June 30, 2020) for the purpose of assessing the potential hydrocarbon resources of the Company’s interests in Botswana and Namibia.

Totten Jr., M., November 16, 2021. “Oil in the Kavango? ALL risk NO reward for Namibia”. Talk presented to the Namibia Scientific Society. The video is here

Viceroy Research Group, 24 June 2021, Recon Africa – no oil? Pump stock; 29 June 2021 ReconAfrica – Con Africa; 30 June 2021, ReconAfrica – Interview w Maggy Shino; 13 July 2021, Africa Good Morning Interview with geologist Jan Arkert; 14 July 2021, Recon Africa – polarization and disengagement. 21 July 2021, ReconAfrica – unpromotional services; 7 September 2021, Another Swing Another Miss

Wanke, A., 2000, Karoo-Etendeka unconformities in NW Namibia and their tectonic implications. PhD Dissertation, University of Wurzburg, 116 pages plus figures.

Wanke, A., H. Stollhofen, I.G. Stanistreet, and V. Lorenz, 2001, Karoo-Etendeka unconformities in NW Namibia and their tectonic implications. Communications Geological Survey of Namibia no. 12, p. 291-301

Werner, M., 2006, The stratigraphy, sedimentology and age of the late Paleozoic Mesosaurus inland sea, SW Gondwana; new implications from studies on sediments and altered pyroclastic layers of the Dwyka and Ecca Group (lower Karoo Supergroup) in southern Namibia. PhD dissertation, Univ. of Wurzburg, 428 p.

York, G. Globe and Mail articles from 2020 an 2021 are linked above in the introduction

EARLIER UPDATES

Update: October 28, 2021

The Botswana Newspaper “Sunday Standard” reports that Recon Africa has been sued in the US for scamming investors. Read the story here. It’s a class action suit submitted by The Klein Law Firm and filed in the US District Court for the Eastern District of New York. Recon Africa reports that one Eric Muller has filed the suit – the company states it will undertake vigorous action to defend itself.

The lawsuit contains 10 claims. Two of the claims pertain to issues that I discussed in this blog post. I support both of these claims: claim no. 1 alleges that ReconAfrica planned to use unconventional means for energy extraction (including fracking) in the fragile Kavango area. Claim no. 8 alleges that ReconAfrica’s interests are in the Owambo Basin, not in the so-called Kavango Basin.

Update: October 20, 2021

On October 14, Prince Harry, the Duke of Sussex, and Namibian Environmental Activist Reinhold Mangundu published an opinion piece in the Washington Post entitled “Protect the Okavango Basin from corporate drilling”

Update: October 10, 2021

On October 8, the Halifax Examiner’s investigative reporter Joan Baxter published an article on ReconAfrica. Full disclosure: I’m quoted. But the article covers a lot more ground than what I could cover here and puts pressure on the Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise to investigate the shady practices of this Canadian company.

Updated September 28, 2021

South African Environmental Law Firm Schindler’s Ecoforensics wrote a letter to Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on May 27 of this year. The letter stresses that Canadian company ReconAfrica acts in violation of international agreements that Canada is signatory to. Copies of the letter were sent to all political party leaders (mr Erin O’Toole, mr Jagmeet Singh and ms Annamie Paul), to ministers Wilkinson (Environment and Climate Change, now minister of Natural Resources) and O’Reagan (Natural Resources) as well as to Elizabeth May (Green Party). Sadly this letter got buried in every addressee’s file cabinet because Canadians haven’t heard anything about it.

Updated August 31, 2021

After 31 years of leaving the local population exposed to unexploded land mines, @ReconAfrica announced on August 31, 2021 that the Namibian police is aiding in land mine removal in the area.

Update August 19, 2021

On August 18, there was presentation to the media about this project in Windhoek, the capital of Namibia. Windhoek-based former petroleum geologist Matthew Totten Jr took the lead in debunking the claims by ReconAfrica. The presentation is here (Matthew Totten starts at minute 7).

Update August 6, 2022

My full comment on the article by Granath, Wanke and Stollhofen, see reference list for complete citation:

The single most important dataset used by Granath et al is the unpublished 2001 PhD dissertation by Wilfried Jooss (University of Würzburg, Germany). The article relies for most of its content on this dissertation. The authors did a bit of additional fieldwork. I find it at least unusual that Wilfried Jooss, about whom I can’t find anything online, is not included as an author. No scientific articles seem to have been published from this dissertation, so the main body of this article relies on untraceable literature (unless you’re willing to pay Amazon for a digital copy). In addition, the authors don’t thank any reviewers, which is highly unusual, to put it mildly.

There are some other unusual errors and omissions in this paper. Figure 1 lacks Lat/Long coordinates and contains an error: the green box doesn’t refer to Figure 2 but to Figure 3. In the caption of Figure 4, it says the white lines are the locations of cross sections depicted in Figures 4 and 5. No, that should have read Figures 5 and 6. A reviewer would have caught these errors.

In the introduction, the authors state: “the Waterberg basin is connected to the NE under Kalahari basin cover to the Kavango Basin through what we call the Omatako trough (Fig. 1)”. They cite the two not peer reviewed extended abstracts by Granath and Dickson (see reference list above) to support this statement. I’m sorry, this is forbidden in scientific practice: you can’t cite literature that hasn’t been peer-reviewed as evidence for something you can’t observe yourself. No Omatako trough is shown on Figure 1 either, but I assume it’s simply the NE-SW valley that the ephemeral Omatako River runs through, joining the Okavango River east of Rundu.

In Fig. 1 the authors draw a tiny dashed line (four dashes!) between the Waterberg area and the Kavango area without telling us what it means. In the text they claim that the features in the Waterberg thrust area are connected to the features further to the NE and reiterate their imaginary Southern Trans-African Rift and Shear System (STARSS) to imply a connection between the Waterberg thrust features and those documented in figure 5. Again: this is whitewashing the two not-peer-reviewed abstracts by Granath and Dickson and that’s forbidden in scientific practice. But by doing so, the authors are seemingly legitimizing the Recon Africa exploration activities (don’t forget that the second author of the article, Ansgar Wanke, who used to be a prof at the university in Windhoek, is now the geologist with Recon Africa).

There is more in this paper that doesn’t meet the requirements of good scientific practice. A paragraph on page 4 cites multiple examples of inversion tectonics elsewhere in the world as supporting evidence for inferred inversion tectonics here. I’m sorry, just because something may have happened in place A, doesn’t mean it happened in the same way in place B. This practice is like saying: “a cow has four legs, hence every 4-legged animal is a cow”. To cover their asses, they admit, on page 11“this prima facie evidence is obviously not present”. Just below this, they go in white-wash overdrive again, citing the hypothetical models proposed in the Granath and Dickson abstracts (again, not peer-reviewed) “in what has been called the Kavango Basin, a group of extensional graben in proprietary seismic data acquired by Reconnaissance Energy Africa”. Let me remind you that a scientific paper should not pass review when it quotes proprietary data that the reader can’t check! Again, was this paper even reviewed?

On page 8, the authors go into speculation overdrive: “Figure 4 postulates the possibility..” to end with “our analysis concludes that the Waterberg Thrust hanging wall and its deformed footwall region are elements of a footwall short cut system in front of the reactivated and inverted deeper growth fault represented by the as-yet-unproven red fault trace”. Excuse me? You spent an appropriate time in the field (we have no idea how much time they spent in the field) and you didn’t check this hypothetical fault trace which is only a few kilometers away from your fieldwork area?

This paper contribute some knowledge to the geologic origin of the enigmatic Waterberg Thrust (except I think the mysterious Wilfried Jooss is the only one who should get credit for the work), but it doesn’t provide any documented geologic evidence that underpins the hydrocarbon exploration program by Recon Africa in the Kavango area: the few off hand references to the Kavango area serve only to whitewash the shoddy geologic underpinning of the Kavango hydrocarbon exploration venture.

A dissertation on the Lower Ecca aged inland sea was completed in 2006. You can see a map on page 27; there are is no sea drawn or a question mark drawn for such a sea in Northeast Namibia. Thank you for your work.

Click to access 00-Complete_thesis-STD.pdf

Thank you! This is clearly a piece of literature that I missed. I will update my blogpost. Be well

Hello Elisabeth,

I am a Canadian who has spent a lot of time in the Kavango region and have been following the ReCon fiasco closely. Your article dated August 2021 is still very relevant and useful; but I wonder if you have updated it more recently? As you may know, ReCon is now moving its activities into Botswana, directly adjacent to the Okavango Delta, a World Heritage Site. A friend who is a petroleum geophysicist maintains that there is no sign of a “working petroleum system” in their latest drilling and seismic data, despite their claims to the contrary. We need to put on the pressure to stop these people, and anything you can add would be appreciated.

Hi, I did send you a reply via e-mail but didn’t hear back, so I’m not sure you got that. In any case – no, I don’t have more information, but I do keep the story more or less updated. I added a few comments recently. And no, none of us geologists think there’s a chance there’s a working petroleum system there. It’s an investment scam.

Thanks. Didn’t get your email but appreciate your comments and updates. Waiting for Recon to implode as their stock value continues its downward trajectory!

I stick with the geology as I have no understanding of the thing called stock market. I do wish the CBC would pay more attention to Canadian resource companies wreaking havoc overseas.

You had me until you write “The world is in a climate crisis and must transition to non-carbon energy as fast as possible”. Sorry but hydrocarbons are here to stay, how do you think solar panels and wind mill parts are made? It’s not from wind or solar power. China is burning more coal than ever making there parts and India will never submit to net zero goals. The IPCC claim of climate crisis is dubious at best. As well, there is not enough cobalt, copper or lithium to achieve net zero goals via solar or wind. Reality bits

Your comment contains only unsubstantiated hearsay, hence I will not approve it.

Your comment doesn’t pertain to this article per se. It’s a broad and not fact-based swipe at those who promote green energy in the best interest of future generations. You don’t include any substantiated critique of my post, hence I will not approve this comment, it’s irrelevant for the ReconAfrica story

Pingback: Oil drilling threatens the Okavango River Basin, putting water in Namibia and Botswana at risk

Pingback: Oil drilling threatens the Okavango River Basin, putting water in Namibia and Botswana at risk - News Oasis

Pingback: Namibia: Oil Drilling Threatens the Okavango River Basin, Putting Water in Namibia and Botswana At Risk – All Namibian Newsfeed

Pingback: Namibia: Oil Drilling Threatens the Okavango River Basin, Putting Water in Namibia and Botswana At Risk – Afro News

Pingback: Oil drilling threatens the Okavango River Basin, putting water in Namibia and Botswana at riskSurina Esterhuyse, Senior Lecturer Centre for Environmental Management, University of the Free State – Alvin M Roman

Pingback: Namibia: Oil Drilling Threatens the Okavango River Basin, Putting Water in Namibia and Botswana At Risk – East Africa Today

Pingback: Oil drilling threatens the Okavango River Basin, putting water in Namibia and Botswana at risk - News Leaflets

Pingback: Oil drilling threatens the Okavango River Basin, putting water in Namibia and Botswana at risk – The Conversation – Engineers Hub

Pingback: Oil Drilling Threatens The Okavango River Basin, Putting Water In Namibia And Botswana At RiskNewsnationmp » NewsNationMp

Pingback: Oil Drilling Threatens the Okavango River Basin, Putting Water in Namibia and Botswana at Risk - African Eye Report

Pingback: Oil Drilling Threatens the Okavango River Basin, Putting Water in Namibia and Botswana at Risk · Fishing Industry News & Aquaculture SA

Pingback: Oil drilling threatens the Okavango River Basin, putting water in Namibia and Botswana at risk – MyDroll

Pingback: Oil drilling threatens the Okavango River Basin, putting water in Namibia and Botswana at risk - Inergency

Pingback: No elephant in this room. – The Data Room

Pingback: No elephant in this room

Pingback: Discord Gods, Part 2 – The Data Room