This article was published in the Halifax Examiner on August 15, 2025

The town of Wolfville is an independent town within the Municipality of Kings County. Windsor is an independent town within Hants County. Both towns are situated on the shore of spectacular Minas Basin, an estuary with tide ranges up to 16m. Both towns are close to the mouth of a tidal river that debouches into the muddy southern side of Minas Basin. Windsor is on the Avon River, Wolfville is on the Cornwallis / Jijuktu’kwek River. Both towns had a natural harbour.

But this is where similarities end.

The Avon River was dammed by a causeway at Windsor in 1971, resulting in man-made Lake Pisiquid, a permanent water body. The lake is nowhere more than 2 ft deep. The aboiteau which enables a bit of water exchange, is open for 10 minutes twice a day. Between March 2021 and June 2023, the aboiteau was permanently open on an order of the Federal Minister of Fisheries and Oceans and a semblance of the original tidal estuary came back to life. But in 2023 Nova Scotia experienced catastrophic forest fires and then-Provincial Minister of Emergency Management John Lohr decreed that a filled Lake Pisiquid was essential as a water source for the fire department, so he ordered the aboiteau back in operation through an emergency measure that the minister must sign off on every two weeks – to this date. The Federal Fisheries Ministers have decided not to intervene. Mi’kmaw protesters camped at the aboiteau for years demanding that the river be allowed to flow naturally so that fish can migrate. To date, the situation in Windsor remains in limbo.

Dried-up Lake Pisiquid on May 29, 2023. The water in the back is the free flowing tidal Avon River. To the right is the dam with stalled construction of the yet-to-be twinned highway 101.

Wolfville has a minuscule harbour that berthed tall ships and steamers until World War 2. It’s not been used since. The rotting remains of the abandoned railway form the southern embankment of the harbour, a construction that’s not up to standards in terms of coastal protection.

The lame duck harbour of Wolfville is celebrated even though it’s just bare mud for all but a few hours a day. For Wolfville to be properly protected from rising sea level and storms, the most rational thing to do would be to close its 500 m harbour entrance by a dyke. Just connect the two dykes that are already there. A “Windsor solution”. Needless to say, this won’t happen. There’s way too much sentimental buy-in for that harbour. Wolfville prefers to risk flooding: high-end condominium construction continues within the downtown flood-prone core.

Sentimentality is partly why lake Pisiquid is maintained: the canoe club, the pumpkin race, the ski hill – those problems are “solved”. The Windsor fire department isn’t worried about having access to enough water, but most citizens of Windsor want their “lake”, whereas the citizens of Wolfville want their “harbour”.

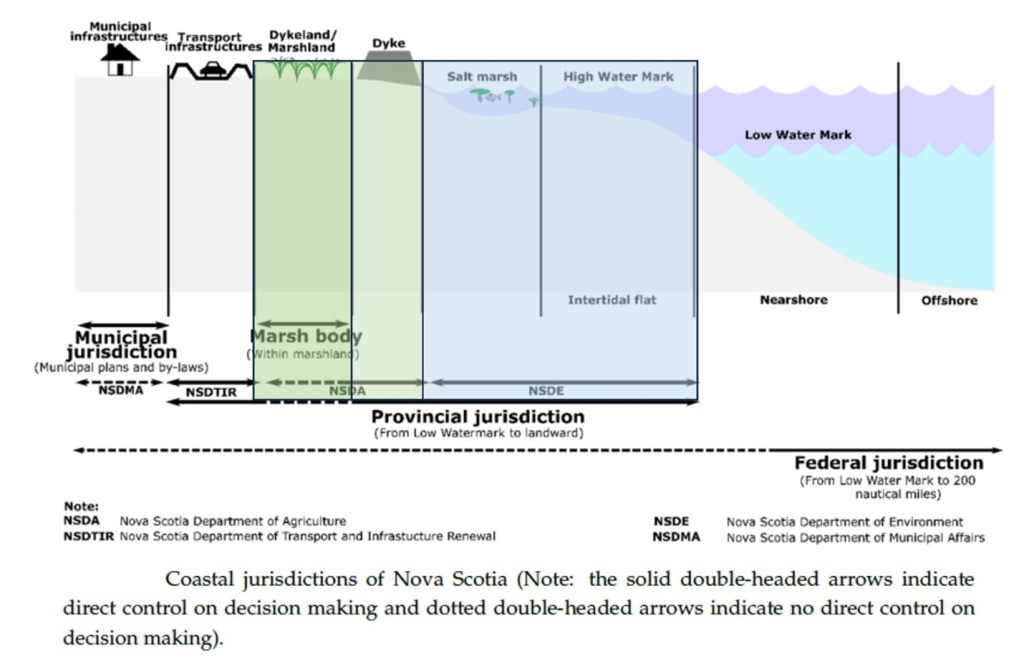

Nova Scotia’s coastal areas and dykelands are managed by a bewildering number of authorities, making for the sort of patchwork decisions illustrated above. The figure below is from a 2019 article by Nova Scotia researchers Rahman, Sherren and Van Proosdij (https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/23/6735): four different Provincial departments, individual Municipalities and the intergovernmental Marsh Body, plus the Federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans all have a say about various skinny intervals in the narrow belt between municipality and the open ocean. If this figure confuses you, you’re not alone.

Because my property borders the Wolfville/Grand Pre dykeland, I get invited to stakeholder meetings about dyke reinforcement by the NS Department of Agriculture (NSDA, green in the diagram). These meetings are attended almost exclusively by dykeland farmers. The superintendent of the Grand Pre National Historic Site usually attends, as does an occasional Municipal councillor and ditto journalist. The discussion – if any – is dominated by farmers expressing concern about losing farmland and NSDA staffers explaining and reassuring them. I have never experienced an open discussion about alternative ways of managing dykeland in cooperation with municipalities: the only debate is ever about maintaining dykeland and securing access for farm equipment. DFO is occasionally mentioned as an irritant (‘they just want fish to migrate’).

I understand farmers’ concerns: they run independent businesses in an increasingly hostile climate, they are on edge, and even more so when faced with inconsistent patchwork policy and partially informed bureaucrats. At one meeting, the NSDA representative presented a dyke realignment proposal for the eastern side of the Grand Pre dykeland and then admitted he had never been there in person (he also admitted he’d grown up in New Ross………).

The surface of the current dykeland lies several meters below the high tide level. The incoming tides leave sediment on the salt marshes on the bay side of the dykes and in this manner these salt marshes maintain themselves at mean high tide level, but the dykeland receives no sediment and has dewatered and compacted as a result of two centuries of farming.

Spring tide, Wolfville dyke: the surface of the dykeland to the right is about 6 feet (1.8m) below the high tide level.

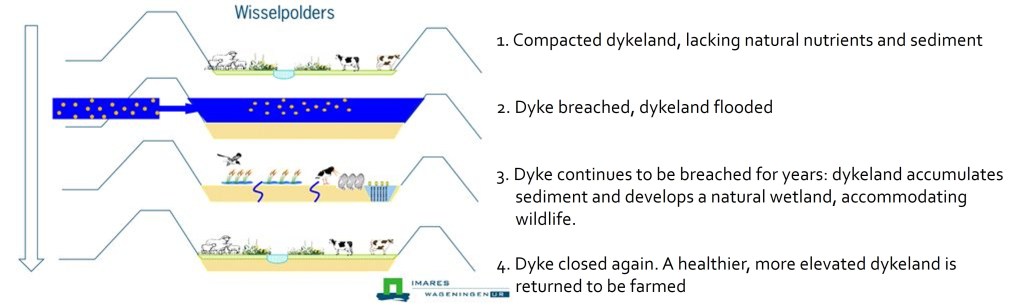

But if sea level rises 1.8 meters (6 feet) before the end of the century, saltwater intrusion in dykeland is only going to get worse, thus limiting potential crops (at present mostly grass, corn and soybeans and an occasional industrial site). The estimated sea level rise is why most dyke levels are scheduled to be increased by 6 feet in the next few years. Many readers will probably think that the Netherlands has practiced agriculture below sea level for centuries so we can surely do that too around Minas Basin? Well, it’s not the same – at all. First of all, the largest tide range along the Dutch coast is just over 4m, about 1/3 of the tidal range in Minas Basin. A lower tide range necessitates lower dykes. In addition, many of the Dutch dykelands exist next to major cities (Rotterdam, Amsterdam, The Hague, Delft) that are crucial economic drivers. No Minas Basin dykeland can make that claim. The Dutch government has changed its approach to dealing with the rising sea from ‘working against nature’ to ‘working with nature’ because the first approach, which they’ve practiced for hundreds of years, is no longer working in an age of rapidly rising sea level. This new approach applies to the entire country, not just to individual municipalities or sections of dykeland. By far the most interesting innovation under this umbrella of innovative measures is the ‘Wisselpolder’, a fabulous term that’s hard to translate. I’ll call it the ‘on-off dykeland’. The practice is shown here

Here in Minas Basin, the difference in elevation between a perigean high tide and the dykeland surface is already quite dramatic and will increase dramatically by mid century, resulting in even more salt water intrusion and a very risky elevation difference between dyke and dykeland. The NS Department of Agriculture – in keeping with the spirit of these times – calls its approach ‘Working with the Tides’, a process that may involve ‘dyke realignment’ (retreat and readjustment) along short, selected stretches. Most dykes, however, will increase massively in height.

Should we really be spending millions of dollars to add 6 feet to dykes that protect small bits of farmland that already struggle with saltwater intrusion, a struggle that will only get worse with higher dykes? Do we really think that an elevation difference of 12 m between high tide and dykeland surface is sustainable? Should we really continue to have seven different authorities work in isolation of each other? Or should we try to come up with comprehensive strategies for the entire basin (such as through a Coastal Protection Act maybe?) to survive this climate-change driven onslaught, working with nature rather than against it everywhere (not just in postage stamp size areas), allowing dykelands to improve with natural sediment (while compensating farmers), and thus create healthier and more robust buffers between the sea and our towns?

Pingback: Minas Basin in a time of climate change and sea level rise – https://jitendra.net.in