Premier Houston demands an oil pipeline

The future is here and it’s mayhem. On March 3, 2025, US President Donald Trump announced a 30% tariff on goods imported from Canada and Mexico, 10% for Alberta oil. The threat had been hanging over our heads ever since he took office, and our political leaders prepared retaliatory tariffs (today, March 6, he announced they won’t go into effect until April, we’ll see). One consequence of this insecure global political situation is that all Canadian jurisdictions are looking closely at how secure they are in terms of food, raw materials and other essentials. And so premier Houston recently announced he’d lift the bans on Uranium mining and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) for natural gas. I disagree with lifting those bans and explained why in my previous post.

The premier has added to the mayhem by throwing out standard democratic processes to access his favourite earth resources.

Then, on February 28, Premier Houston wrote a scathing letter to Bloc Québécois Leader Yves-François Blanchet, blaming him for resisting the idea of an oil pipeline from Alberta through Québec to Atlantic Canada. Speaking to reporters in Québec in February, Mr Blanchet said: “We are fiercely opposed to any type of transport on Québec territory of hydrocarbons from Western Canada to any market whatsoever. It does not serve Québec. It does not serve the environment. It does not serve the planet”. Premier Houston wrote to Mr Blanchet “you made these comments in respect to the resurrection of an Energy East type project wherein energy would be transported from Western Canada to Eastern Canada” and then blamed Blanchet for “disparaging opportunities for energy security for all Canadians and alienating Atlantic Canada”.

First the wording. Blanchet uses the term ‘hydrocarbons’, a catch-all term for any type of oil or gas. Houston uses the term ‘energy’. Blanchet’s terminology is correct, Houston’s is not. Pipelines transport hydrocarbons, they don’t transport energy. Energy is what you get when you install equipment to burn refined hydrocarbons.

I live on a busy road and see and hear the oil trucks. They burn lots of gasoline to drive all across the Province to fill home oil tanks, an incredibly inefficient method. Only in this northeastern corner of the continent do as much as 40% of homes still heat with oil. I can’t stop being surprised that this practice still exists (full disclosure: our 72 year old house never had an oil tank). And of course Nova Scotians burn lots of gasoline in their vehicles because we have little public transport outside HRM and half our population is scattered all over the Province and electric vehicles and hybrids are expensive and hard to come by.

About 2.5 million people live in Atlantic Canada, which covers an area three quarters the size of Manitoba, and that includes all that water between our four Provinces. Compare this with for example Manitoba, which has 2 million people, half of them in Winnipeg in its far southeastern corner. Atlantic Canadians are on average a lot less accessible than Manitobans. Atlantic Canada and Quebec are insecure when it comes to fossil fuel supply. We don’t have the stuff ourselves (geology) and we’re a widely dispersed population at the edge of the continent (geography). But does that mean we need a pipeline?

Canada as an oil producer

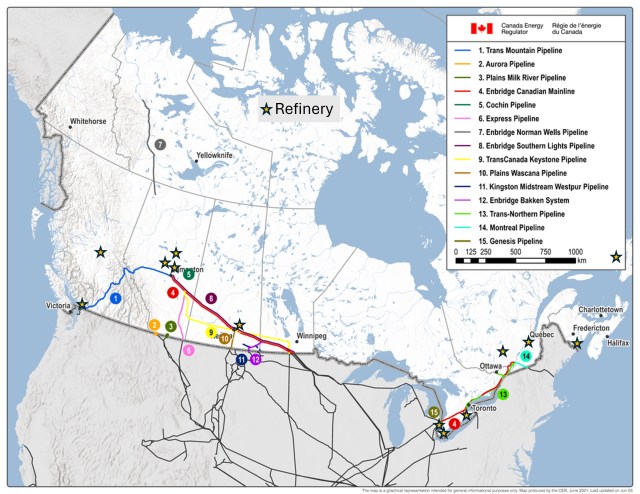

Canada is the world’s fourth largest hydrocarbon producer; most of this reserve is in Alberta, lesser amounts are in Saskatchewan, western Manitoba and northeastern British Columbia. Oil and gas are transported by rail and by pipeline from Alberta to Vancouver (which tripled transport capacity after the completion of the Trans Mountain II pipeline this year).

Oil and gas are also transported into the US and as far east as Montreal. From Montreal, a pipeline runs to Portland (Maine) from where oil is shipped out because Maine doesn’t have refineries. This pipeline was built during World War II and parallels a pre-existing rail line, so it was relatively easy to construct in a time of crisis. The distance from Montreal to Portland is 1/3 of the distance from Montreal to Saint John or Halifax.

Most Alberta heavy crude is refined in the US. Canada has refineries, but they can’t process heavy crude, so they process light crude from the US. Don’t ask me why. When Prime Minister Stephen Harper originally proposed the Energy East pipeline as a way of transporting heavy Alberta crude to eastern Canada, the Irving Refinery in Saint John made clear that they wouldn’t be able to process it without retrofitting and expanding the refinery (and please give us the money to do so).

This was altogether aside from the fact that the existing pipeline would have to be completely retrofitted as well, to some extent rerouted and then extended, and that not only Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick would have to agree on all aspects of that engineering process (assuming that Saskatchewan and Manitoba would agree), but also 180 First Nations through whose territories it would run. And – minor detail – it’s four times as far from Alberta to Saint John as it is from Alberta to Vancouver

Why do planned pipelines fail?

Pipelines take a long time and a lot of money to build. Investment in pipelines (government loans, grants and tax breaks, shares in the private market) is based on expected future returns.

But if you would include the long-term well-being of communities and the potential effects on biodiversity, air quality and aquatic health along a pipeline into its financial picture, the investment opportunity would begin to look different. Considering natural resources only in terms of financial assets and potential accumulation of wealth through resource extraction, ignores the importance of long-term ecological well being for people and the planet. It’s these more intangible assets that are the addressed mostly by environmental NFPs and, in Canada, by Indigenous Nations.

Let’s consider the failed Northern Gateway pipeline. Enbridge and its shareholders never lost money even though the pipeline never materialized. To garner support for the planned pipeline, Enbridge played on sentiments of future perceived wealth for communities along its route. But in the end, unresolved land claim disputes became mixed up with these imagined returns and Indigenous Nations simply couldn’t be seduced with just more money. They valued the intangible benefits of their existing way of life above the potential economic benefits of the pipeline. But years later after failing to materialize, Enbridge is alive and well and continues to trade on the stock market. Companies like this create complex financial and corporate structures that keep them afloat even when they make no money – all the while battling civil society groups that don’t have that kind of financial back-up. In other words, such a dispute is never a level playing field: one partner can rely on vast resources to push its agenda, while the other partner relies on volunteer work and free will donations.

Or consider the Trans Mountain / Kinder Morgan pipeline that eventually did get built, it runs parallel to an existing pipeline. Kinder Morgan had its headquarters in Texas and traded on the US stock exchange. Delays and conflict led to the Canadian government buying it for $4.5 billion. Trans Mountain shareholders rejoiced! Its eventual construction cost Canadian taxpayers about $16 billion and faced lots of protests (in vain) by First Nations and civil groups. The financial expense of this pipeline wasn’t just carried by a private company and its shareholders, but by all Canadians in a process that transferred private to public (you and my) debt. Trans Mountain II is an excellent example of a failed private investment project that resulted in really good returns for private investors but a decades long debt for civil society.

Private citizens buy assets and can borrow money to do so if it’s considered a good investment: homes, cars, businesses. People look after their investments so they might gain value, justifying the loan and the interest. Building a pipeline requires massive investments. The only way to justify those investments is if there is a healthy Return on Investment. In other words: if you build a pipeline, you must use it for a very long time.

Global temperatures are rising rapidly because of massive fossil fuel burning. Already the effects of man-made climate change are felt daily around the world. Averting the worst effects of global climate change means that we must change to other sources of energy as fast as possible. This is not an easy task. But investing in a fossil fuel pipeline is definitely the wrong idea, it’s a way to turn the clock back, especially when it’s unlikely the stuff going through that pipeline would benefit people of Atlantic Canada.

Conclusion

Yes, Atlantic Canadians are energy-insecure when you consider only fossil-fueled energy. But building a hydrocarbon pipeline isn’t going to solve that problem.

I agree with mr Blanchet: Energy East would not serve Québec or Atlantic Canada, it would not serve the environment and it would not serve the planet. Prove me wrong, mr Houston.

References

Government of Canada sites 1, 2, 3

Janzwood, A., Neville, K. and Martin, S., 2023, Financing energy futures: the contested assetization of pipelines in Canada, Review of International Political Economy, v. 30 no. 6, p. 2333-2356.